Steven Hill’s family, Taylor Sherrell (left), Hailey Horner and Kado Bissell gather around Hill’s urn in front of his family’s home in Tulsa. DYLAN GOFORTH/The Frontier

She had waited almost two years, but it was finally time to disconnect her son’s cellphone.

Cheryl Horner liked to call Steven Hill occasionally, though she knew he wouldn’t answer. Her son died in 2017, but she called to listen to his greeting on the voicemail. It was just nice to hear his voice.

The family recently had the phone shut off, but they keep an end table in the living room that serves as a memorial to the 17-year-old. There are photos of Hill and a colorful plaque that friends and family signed at his memorial. He loved Scooby Doo, so they put a toy Mystery Machine van on the table, too.

About two years ago, Horner woke up at about 4 a.m. to get ready for work. She walked by Hill’s room, but his bed was empty and the light was on. As she made her way to the living room she saw red and blue flashing lights creeping through the windows. On the TV, she noticed her north Tulsa street was on the news.

Then she heard the sound of officers knocking at her door. She dropped to her knees. Her stomach sank.

“I already knew. I already knew. I don’t know how I knew, but I knew,” Horner said.

Kado Bissell holds a photo of Steven Hill, who died in 2017 from a firearm injury. DYLAN GOFORTH/The Frontier

Her son had been in the neighbor’s garage hanging out with friends when a shotgun reportedly fell from another teen’s lap. While trying to catch it, Hill’s friend discharged the gun, shooting Hill in the head, according to reports from the incident.

Hill was pronounced dead at the scene, and the shooting was later ruled an accident.

“Steven was a good kid. He always had a smile on his face,” Horner said. “He always loved people. I don’t know — it’s just — it’s devastating. And you never even know how bad it is until it happens to you.”

Horner’s son is one of hundreds of Oklahoma youth who have died from a gun injury since 2000.

The Frontier analyzed data from the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Oklahoma Health Care Authority and Department of Health to determine how many youth age 17 and younger had been injured or killed by firearms.

Dozens of children are injured or killed by firearms each year, but no single state agency keep track of them all. Ask agencies how many children are hurt by firearms and no one knows.

The state’s health department tracks firearm deaths, but has no programs to try to prevent them. State leaders say there are two main reasons for the lack of prevention programs — politics and a lack of funding.

The Frontier’s analysis found that since 2000 at least 467 Oklahoma youth have died from firearm injuries — state agencies categorized those deaths as accidental, intentional or self-injuries.

From 2000 to 2017, pediatric firearm deaths in Oklahoma increased by 78 percent. In 2000, two children were fatally shot for every 10,000. By 2017, that number had grown to 3.3 deaths per 10,000 children. These numbers take into account Oklahoma’s population growth over the same time period.

Pediatric firearm deaths reached a 16-year high in 2016 when 32 kids died, and the same number died in 2017, The Frontier found. The year with the fewest deaths was 2000, when 18 youth were fatally shot. State Medical Examiner data for 2018 was incomplete.

They happened across the state — from Guthrie, to Tulsa, to Bokoshe. The most common place of death was in homes, but children also died from gunshots in streets, fields and in cars.

In the medical examiner’s data, deaths were usually categorized as a homicide, suicide or accident, but sometimes the shooter’s intent was unknown.

The deaths happened across all ages. The median age was 15, but the youngest was only a few months old. Two-thirds of the youth were age 15 or older, but 51 of the kids were less than 10.

Boys were more likely to be fatally shot than girls, making up about 83 percent of the dead.

In 2016, children of color were two-and-a-half times more likely to be victims of firearm homicide than white children, the analysis showed.

On average, 26 children were fatally shot each year, The Frontier’s analysis found. Homicides made up the largest portion of the deaths at 44 percent, followed by self-injuries, while accidents made up the smallest portion.

Oklahoma’s Child Death Review Board issues recommendations to the Legislature and state agencies each year. The board once made firearm deaths a priority, but despite the increase of fatal shootings, the agency has made no mention of the issue in its annual recommendations for more than a decade.

Firearms killed more youth than child abuse and neglect did in 2016, but less than car crashes, data showed.

Many more children were injured by firearms between 2000 and 2017, but exactly how many is unclear. No single state agency tracks all the data.

The Oklahoma State Department of Health’s Injury Prevention Service program tracks how many children were treated in hospitals for firearm injuries, but that data does not include emergency room or doctor’s office visits.

From 2007 to 2015, the agency recorded 321 youth discharged from hospitals after being treated for firearm injuries. The vast majority of those were caused by accidents or assaults.

The agency declined to provide data beyond 2015, citing national changes to the way firearm injuries are classified.

Meanwhile, Oklahoma’s Medicaid program, SoonerCare, approved claims for 185 youth treated for firearm injuries in 2012, and for 241 children in 2017. That data included children treated in emergency rooms, doctors’ offices and even follow-up visits. However, it only captured youth who participated in the SoonerCare program.

From January 2012 to December 2018, SoonerCare paid out more than $5.5 million for treatment of pediatric firearm injuries, according to data provided by the Oklahoma Health Care Authority. Medicaid uses state and federal money to offer health coverage, and uses a fee-for-service system to reimburse providers for procedures.

The majority of injuries stemmed from accidents.

That was the case with Andrew White.

White often visited his great-grandmother’s neighbor, Boone Buben, at his home in Chickasha to chat and play video games. That’s what the 13-year old-was doing when he was shot and killed on May 30, 2017.

White had just arrived at Buben’s home when the man went to put his pistol in a safe. Buben, who told police he did not think the gun was loaded, pointed it at the boy and pulled the trigger, according to records filed in the case.

White was pronounced dead at the scene.

Buben, 33, pleaded guilty to second-degree manslaughter in 2018. The state Medical Examiner’s Office ruled White’s death a homicide.

White’s grandmother, Gail White, had been raising the boy. She died in late 2017.

“He would tell me how much he loved me. I’d say ‘I love you,’ and he’d say ‘I love you more,'” Gail White told The Oklahoman in 2017. “I really miss him already. His life shouldn’t have ended this young.”

***

Oklahoma saw its highest number of recorded youth gun homicides since 2008 in 2016 with 14 deaths. That number remained steady in 2017.

Jimmy Foreman, a youth minister at Sandusky Ave. Christian Church and chaplain with the Tulsa Police Department, works with and mentors at-risk youth in the Tulsa area every day.

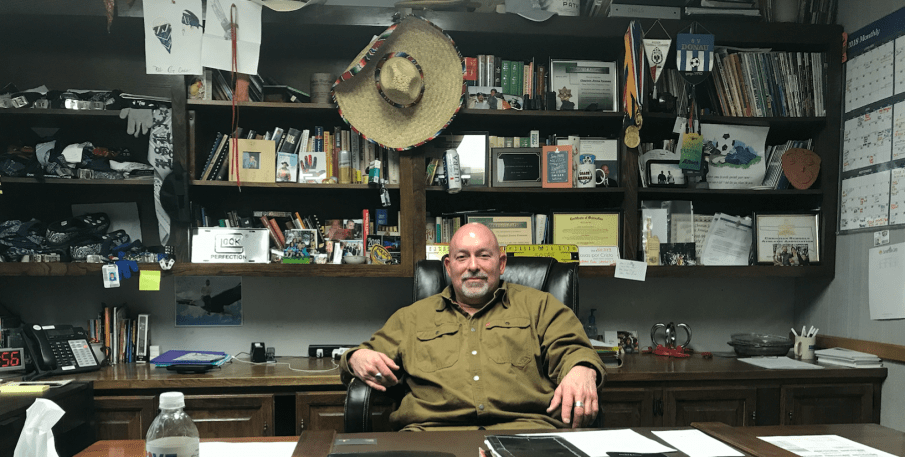

Gang paraphernalia he has confiscated from them hang from the walls of his office at a church in midtown. Among the items, old newspaper articles that have started to yellow from age serve as reminders of the kids Foreman was able to help save, and the ones he couldn’t.

Jimmy Foreman, a youth minister at Sandusky Ave. Christian Church and chaplain with the Tulsa Police Department, mentors at-risk teenagers. KASSIE McCLUNG/The Frontier

Pictures of children he has mentored can be found around his desk — some of them are dead.

“Unfortunately, since I’ve been a youth minister since ‘99, I’ve lost five kids, which is crazy,” Foreman said. “If you throw car accidents in there, I’ve lost a lot more. But just to gun violence, five.”

As a chaplain, Forman said he is called out on cases where kids die from gun injuries several times each year. Though he considers himself a gun enthusiast, he maintains the importance of handling them responsibly.

“I’ve been doing this for years, and I still don’t know how to stop it,” Foreman said of the deaths.

“In an ideal world, it would be good to have them be taught gun safety so they’d know how important that is because a lot of this, what I’ve worked this year, could have been prevented.”

Sometimes the children killed by firearms were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, caught in unintentional crossfire or mistaken for the intended target.

Other times, the intent of the shooter was unknown.

Oklahoma City police were never able to identify the person who shot Isjanna James.

Isjanna was shot on Feb. 26, 2007, in her grandmother’s home in Oklahoma City. The 8-month-old was asleep on a couch when gunshots rang out and a bullet tore into the house. Police said it was a drive-by shooting.

Isjanna James was shot in the head in a drive-by shooting in Oklahoma City. She died in 2017 at age 10. Photo Courtesy of News9.

Garvenia James, Isjanna’s grandmother, realized the baby had been shot in the head. The injury left Isjanna paralyzed.

She died in April 2017 at age 10.

The Medical Examiner’s Office determined her death was caused by complications related to the gunshot wound . No arrest was ever made for the shooting.

Garvenia James said her family has not been able to get closure. She raised Isjanna after the incident, ensured the girl got to a school tailored to her special needs and saw that she stayed on the medication that stopped the seizures that started after the shooting.

“We took the best care of her we could,” Garvenia James said. “We enjoyed her as long as God let us. She was a blessed child. We were blessed to have her.

“We just miss her.”

***

State agencies have programs that monitor firearm deaths, but none to try to prevent them.

The Oklahoma State Health Department has an Injury Prevention Service division, but its programs do not focus on firearm injury prevention. Instead, the program is geared toward drownings, fire-related injuries and properly installing children’s car seats.

The agency takes part in the National Violent Death Reporting System, a Centers for Disease Control & Prevention surveillance program that collects data on violent deaths from more than 40 states.

The health department’s division does have a couple of fact sheets on safety around firearms.

“Guns may seem fun in movies or games, but real guns are not toys and can cause serious, permanent injuries or even death,” one states.

Health department spokesman Tony Sellars said the federal funding that allows the agency to collect data on firearm deaths can only be used for surveillance, not prevention.

“We do not have any funding currently that enables us to develop/implement any firearm-related initiatives/campaigns,” he wrote in an email.

Federal research into gun violence has been essentially halted since the mid-90s when the National Rifle Association sought a measure to stop federal funds from going to the CDC that were used to pay for research on gun injuries and deaths.

In a spending bill last year Congress made changes that would allow the CDC to study gun violence. However, that has yet to lead to a hike in federal research.

Oklahoma’s Child Death Review Board studies cases of pediatric fatalities and issues recommendations annually to the Legislature and state agencies in an effort to reduce preventable child deaths. The Oklahoma Commission on Children and Youth (OCCY) oversees the board.

In recommendation reports in 2003, 2004 and 2005, board members made pediatric firearm deaths one of their top priorities. In 2004, firearm deaths represented 7 percent of all cases the board reviewed.

Among the board’s recommendations were mandatory sobriety testing for anyone present during a firearm fatality, development of gun safety and avoidance programs, and continued support for then Lt. Gov. Mary Fallin’s gun lock giveaway program.

Despite the increase, there has been no mention of pediatric firearm deaths in the board’s recommendations since 2005. Instead, the board’s 2017 report included recommendations on mental health assessments, traffic-related deaths and safe sleep environments for infants.

“Actually, it was probably just a lot to do with the climate around the topic. But we didn’t have a discussion about, let’s drop this (firearm recommendations) at all,” said Lisa Rhoades, the Child Death Review Board’s program manager.

OCCY director Annette Jacobi said infant deaths due to unsafe sleep environments took over as a priority for the board in the early 2000s. The board reviewed 73 cases in 2016. A focus has also been on vehicular deaths, she said.

The board reviewed 91 vehicle-related deaths in 2004 and 35 in 2016.

“And it’s not that we don’t care about firearms,” Jacobi said. “It’s just that there are policies and practices that state agencies can really become involved in and make a difference in, and those two areas maybe more so than the gun issue.”

The board reviewed 19 firearm deaths in 2016, while the medical examiner’s office recorded 32. Rhoades said she has essentially been overseeing the board’s operations by herself since 2015, when she lost her assistants because of state budget cuts. Because of that, the board doesn’t have real-time data.

Jacobi said the board isn’t able to review every pediatric death.

“If there are 650 deaths in a given year or so, in general, anywhere from 200 to 300 of those cases get reviewed by child death review board,” Jacobi said. “We want to review them all, but it’s just not humanly possible with only one person.”

State agencies are also more likely to have resources to put into other issues, Jacobi said.

“I think, you know, oftentimes the issue we focus on somewhat are driven by the funding stream,” she said. “But in addition, I think it’s fair to say if you’re looking at wanting to make a big impact, safe sleep and motor vehicle deaths are the leading cause, so that’s where a lot of the time and attention go.”

***

There is no fresh or reliable data on firearm ownership in Oklahoma, but studies suggest almost one-third of households own at least one.

The risk of children dying by suicide is four to 10 times higher in homes with guns, according to The American Academy of Pediatrics. Meanwhile, gun ownership in the U.S. has increased over the last two decades.

John Donohue is a law professor at Stanford Law School where he researches gun violence. He said research has shown that in states where gun prevalence is high, so are gun suicides.

“I think in gun communities where suicides are rising substantially, it’s again sort of a double whammy because the general people aren’t wanting to talk about suicide,” Donohue said. “Gun owners and gun enthusiasts aren’t all that (eager) to acknowledge the impact.”

He said across the country, data for firearm injuries is lacking.

Gun suicides hit a 17-year high in Oklahoma in 2016 when 18 youth died, medical examiner data shows.

Shelby Rowe is the youth suicide prevention program manager at the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services. She said the program encourages parents and guardians to safely store firearms. That includes pointing people to Project ChildSafe, a national safety campaign.

Oklahoma City officials partnered with Project ChildSafe in 2017 to give away firearm safety kits that include a cable-style gun lock and safety brochure. The locks are available in law enforcement agencies across the state, said Bill Brassard, senior director of communications for the National Shooting Sports Foundation, which oversees the program.

The campaign also encourages the use of safes for owners who do not wish to keep the locking device on their firearms.

“It’s not a gun control program at all,” Brassard said. “It’s responsible gun ownership. … And the vast majority of gun owners are responsible, but we want to remind people nevertheless to take stock of how they’re storing their firearms at home and in vehicles.”

Mike Brose is the chief empowerment officer at Mental Health Association Oklahoma. He said the organization has long promoted the use of gun locks and occasionally gives them away.

Mike Brose, CEO of Mental Health Oklahoma, speaks at the unveiling of the “Too Big To Ignore” mural in Tulsa in May 2017. KASSIE McCLUNG/The Frontier

Brose said when people who are suicidal call into the organization, one of the first questions employees ask is: Do you have a firearm in the house?

“What the research says is that a very sizeable number of people who would be suicidal will move past that and be in a better state of mind, or they’ll move through and start to think about other options,” Brose said. “But if you have access to a firearm it’s fast, and it’s very lethal.”

Brose said he believes the state’s lack of action on firearm injury prevention stems from the fear of ramifications.

“I don’t think we need to go out and take everyone’s guns away,” Brose said. “But I tell you, we need to do something about the number of people who are killing themselves with firearms.

“There is no reason, none, for a child to kill themselves. Now as an adult, I know that and I bet you 99.999 percent of people in this country would agree with that. But yet, we don’t really do all that we should and could do to prevent either accidental death, getting ahold of a gun or dying by suicide because you see that as your only alternative.”

***

Resources

If you or someone you know is in an emergency, you can call or chat online with a counselor on The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24/7. Call 800-273-TALK (8255) or call 911 immediately.

Know The Warning Signs

- Threats or comments about killing themselves, also known as suicidal ideation, can begin with seemingly harmless thoughts like “I wish I wasn’t here” but can become more overt and dangerous

- Increased alcohol and drug use

- Aggressive behavior

- Social withdrawal from friends, family and the community

- Dramatic mood swings

- Talking, writing or thinking about death

- Impulsive or reckless behavior

Project ChildSafe has resources on firearm safety and how to find a safety kit.